#they are so important to the ecology of north america

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The blurb does not detail the true spirit of 42f. 21m joined the pack as the mate of former alpha female 40f, 42f's sister. 40f was known for violence and killing other female's pups. 21m bred with 40f, 42f, and their niece, and all three female had pups. 40f decided to beat up 42f, as she often did, and then follow her back to her den, likely to kill 42f's pups. 42f defended her pups and turned on her sister, and got the support of several other wolves to attack 40f, who later died from her injuries. 42f moved her pups into 40f's den, with 40f's pups being raised as her own. She also allowed her niece to share the den and all the females' pups were raised communally. This is likely why so many pups survived, because all were fed and cared for by the entire pack and two loving mothers.

#wolves#yellowstone wolves#return wolves to protected status#they are being massacred by trophy hunters#they are so important to the ecology of north america#deer coyotes and feral dogs would all be kept in check by wolves#which are extremely shy of humans and are a minimal threat to us

80K notes

·

View notes

Text

There was this post a while ago where somebody was saying that Cheetahs aren't well suited to Africa and would do well in Midwestern North America, and it reminded me of Paul S. Martin, the guy I'm always pissed off about.

He had some good ideas, but he is most importantly responsible for the overkill hypothesis (idea that humans caused the end-Pleistocene extinctions and that climate was minimally a factor) which led to the idea of Pleistocene rewilding.

...Basically this guy thought we should introduce lions, cheetahs, camels, and other animals to North America to "rewild" the landscape to what it was like pre-human habitation, and was a major advocate for re-creating mammoths.

Why am I pissed off about him? Well he denied that there were humans in North America prior to the Clovis culture, which it's pretty well established now that there were pre-Clovis inhabitants, and in general promoted the idea that the earliest inhabitants of North America exterminated the ecosystem through destructive and greedy practices...

...which has become "common knowledge" and used as evidence for anyone who wants to argue that Native Americans are "Not So Innocent, Actually" and the mass slaughter and ecosystem devastation caused by colonialism was just what humans naturally do when encountering a new environment, instead of a genocidal campaign to destroy pre-existing ways of life and brutally exploit the resources of the land.

It basically gives the impression that the exploitative and destructive relationship to land is "human nature" and normal, which erases every culture that defies this characterization, and also erases the way indigenous people are important to ecosystems, and promotes the idea of "empty" human-less ecosystems as the natural "wild" state.

And also Martin viewed the Americas' fauna as essentially impoverished, broken and incomplete, compared with Africa which has much more species of large mammals, which is glossing over the uniqueness of North American ecosystems and the uniqueness of each species, such as how important keystone species like bison and wolves are.

It's also ignoring the taxa and biomes that ARE extraordinarily diverse in North America, for example the Appalachian Mountains are one of the most biodiverse temperate forests on Earth, the Southeastern United States has the Earth's most biodiverse freshwater ecosystems, and both of these areas are also a major global hotspot for amphibian biodiversity and lichen biodiversity. Large mammals aren't automatically the most important. With South America, well...the Amazon Rainforest, the Brazilian Cerrado and the Pantanal wetlands are basically THE biodiversity hotspot of EVERYTHING excepting large mammals.

It's not HIM I have a problem with per se. It's the way his ideas have become so widely distributed in pop culture and given people a muddled and warped idea of ecology.

If people think North America was essentially a broken ecosystem missing tons of key animals 500 years ago, they won't recognize how harmful colonization was to the ecosystem or the importance of fixing the harm. Who cares if bison are a keystone species, North America won't be "fixed" until we bring back camels and cheetahs...right?

And by the way, there never were "cheetahs" in North America, Miracinonyx was a different genus and was more similar to cougars than cheetahs, and didn't have the hunting strategy of cheetahs, so putting African cheetahs in North America wouldn't "rewild" anything.

Also people think its a good idea to bring back mammoths, which is...no. First of all, it wouldn't be "bringing back mammoths," it would be genetically engineering extant elephants to express some mammoth genes that code for key traits, and second of all, the ecosystem that contained them doesn't exist anymore, and ultimately it would be really cruel to do this with an intelligent, social animal. The technology that would be used for this is much better used to "bring back" genetic diversity that has been lost from extant critically endangered species.

I think mustangs should get to stay in North America, they're already here and they are very culturally important to indigenous groups. And I think it's pretty rad that Scimitar-horned Oryx were brought back in their native habitat only because there was a population of them in Texas. But we desperately, DESPERATELY need to re-wild bison, wolves, elk, and cougars across most of their former range before we can think about introducing camels.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyway while we're on the subject of public misconception towards living things (which is completely understandable because have you SEEN living things? There's like dozens of them!) here's a fresh rundown of some common mistakes about bugs!

Arachnids aren't just spiders! They're also scorpions, mites, ticks and some real weirdos out there

Insects with wings are always finished growing! Wings are the last new thing they ever develop! There can never be a "baby bee" that's just a smaller bee flying around.

That said, not all insects have larvae! Many older insect groups do look like little versions of adults....but the wings rule still applies.

Insects do have brains! Lobes and everything!

Only the Hymenoptera (bees, ants and wasps) have stingers like that.

Not all bees and wasps live in colonies with queens

The only non-hymenoptera with queens are termites, which is convergent evolution, because termites are a type of cockroach!

There are still other insects with colonial lifestyles to various degrees which can include special reproductive castes, just not the whole "queen" setup.

Even ants still deviate from that; there are multi-queen ant species, some species where the whole colony is just females who clone themselves and other outliers

There is no "hive mind;" social insects coordinate no differently from schools of fish, flocks of birds, or for that matter crowds of humans! They're just following the same signals together and communicating to each other!

Not all mosquito species carry disease, and not all of them bite people

Mosquitoes ARE ecologically very important and nobody in science ever actually said otherwise

The bite of a black widow is so rarely deadly that the United States doesn't bother stocking antivenin despite hundreds of reported bites per year. It just feels really really bad and they give you painkillers.

Recluse venom does damage skin, but only in the tiny area surrounding the bite. More serious cases are due to this dead skin inviting bacterial infection, and in fact our hospitals don't carry recluse antivenin either; they just prescribe powerful antibiotics, which has been fully effective at treating confirmed bites.

Bed bugs are real actual specific insects

"Cooties" basically are, too; it's old slang for lice

Crane flies aren't "mosquito hawks;" they actually don't eat at all!

Hobo spiders aren't really found to have a dangerous bite, leaving only widows and recluses as North America's "medically significant" spiders

Domestic honeybees actually kill far more people than hornets, including everywhere the giant "murder" hornet naturally occurs.

Wasps are only "less efficient" pollinators in that less pollen sticks to them per wasp. They are still absolutely critical pollinators and many flowers are pollinated by wasps exclusively.

Flies are also as important or more important to pollination than bees.

For "per insect" pollination efficiency it's now believed that moths also beat bees

Honeybees are non-native to most of the world and not great for the local ecosystem, they're just essential to us and our food industry

Getting a botfly is unpleasant and can become painful, but they aren't actually dangerous and they don't eat your flesh; they essentially push the flesh out of the way to create a chamber and they feed on fluids your immune system keeps making in response to the intrusion. They also keep this chamber free of bacterial infection because that would harm them too!

Botflies also exist in most parts of the world, but only one species specializes partially in humans (and primates in general, but can make do with a few other hosts)

"Kissing bugs" are a group of a couple unusual species of assassin bug. Only the kissing bugs evolved to feed on blood; other assassin bugs just eat other insects.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Starting this month [June 2024], thousands of young people will begin doing climate-related work around the West as part of a new service-based federal jobs program, the American Climate Corps, or ACC. The jobs they do will vary, from wildland firefighters and “lawn busters” to urban farm fellows and traditional ecological knowledge stewards. Some will work on food security or energy conservation in cities, while others will tackle invasive species and stream restoration on public land.

The Climate Corps was modeled on Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, with the goal of eventually creating tens of thousands of jobs while simultaneously addressing the impacts of climate change.

Applications were released on Earth Day, and Maggie Thomas, President Joe Biden’s special assistant on climate, told High Country News that the program’s website has already had hundreds of thousands of views. Since its launch, nearly 250 jobs across the West have been posted, accounting for more than half of all the listed ACC positions.

“Obviously, the West is facing tremendous impacts of climate change,” Thomas said. “It’s changing faster than many other parts of the country. If you look at wildfire, if you look at extreme heat, there are so many impacts. I think that there’s a huge role for the American Climate Corps to be tackling those crises.”

Most of the current positions are staffed through state or nonprofit entities, such as the Montana Conservation Corps or Great Basin Institute, many of which work in partnership with federal agencies that manage public lands across the West. In New Mexico, for example, members of Conservation Legacy’s Ecological Monitoring Crew will help the Bureau of Land Management collect soil and vegetation data. In Oregon, young people will join the U.S. Department of Agriculture, working in firefighting, fuel reduction and timber management in national forests.

New jobs are being added regularly. Deadlines for summer positions have largely passed, but new postings for hundreds more positions are due later this year or on a rolling basis, such as the Working Lands Program, which is focused on “climate-smart agriculture.” ...

On the ACC website, applicants can sort jobs by state, work environment and focus area, such as “Indigenous knowledge reclamation” or “food waste reduction.” Job descriptions include an hourly pay equivalent — some corps jobs pay weekly or term-based stipends instead of an hourly wage — and benefits. The site is fairly user-friendly, in part owing to suggestions made by the young people who participated in the ACC listening sessions earlier this year...

The sessions helped determine other priorities as well, Thomas said, including creating good-paying jobs that could lead to long-term careers, as well as alignment with the president’s Justice40 initiative, which mandates that at least 40% of federal climate funds must go to marginalized communities that are disproportionately impacted by climate change and pollution.

High Country News found that 30% of jobs listed across the West have explicit justice and equity language, from affordable housing in low-income communities to Indigenous knowledge and cultural reclamation for Native youth...

While the administration aims for all positions to pay at least $15 an hour, the lowest-paid position in the West is currently listed at $11 an hour. Benefits also vary widely, though most include an education benefit, and, in some cases, health care, child care and housing.

All corps members will have access to pre-apprenticeship curriculum through the North America’s Building Trades Union. Matthew Mayers, director of the Green Workers Alliance, called this an important step for young people who want to pursue union jobs in renewable energy. Some members will also be eligible for the federal pathways program, which was recently expanded to increase opportunities for permanent positions in the federal government...

“To think that there will be young people in every community across the country working on climate solutions and really being equipped with the tools they need to succeed in the workforce of the future,” Thomas said, “to me, that is going to be an incredible thing to see.”"

-via High Country News, June 6, 2024

--

Note: You can browse Climate Corps job postings here, on the Climate Corps website. There are currently 314 jobs posted at time of writing!

Also, it says the goal is to pay at least $15 an hour for all jobs (not 100% meeting that goal rn), but lots of postings pay higher than that, including some over $20/hour!!

#climate corps#climate change#climate activism#climate action#united states#us politics#biden#biden administration#democratic party#environment#environmental news#climate resilience#climate crisis#environmentalism#climate solutions#jobbs#climate news#job search#employment#americorps#good news#hope

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

What is our ecological responsibility when encountering an invasive animal species?

that depends on what that species is, and im struggling to come up with any catch-all response to that. there are a lot types of animals.

some stuff is way beyond our control, like the invasion of earthworms into North America and many other invertebrate species—it would be just as much of a waste of effort trying to kill all the spotted lanternflies as it would be to dig up every worm in the forest.

for stuff like fish, cats, and hogs… I really don’t know. this isn’t my area of expertise but I do think invasive mammals are at least a little easier to exclude/control/manage through hunting and trapping than minute flying or soil borne invertebrates (maybe not the hogs. they sound unstoppable). also people tend to get very stupid when it concerns charismatic or domesticated megafauna, even if vulnerable native ecology is at stake.

in all cases, prevention is most important: don’t let pets loose, make note of unfamiliar insects or help to track the spread of establishing species.

I also think it is important to not demonize or abuse the invasive animals regardless of what we need to do to control them. they’re not evil, they’re just trying to survive—torturing them doesn’t accomplish anything. so even if cane toads and cats and horses *AND pythons and fish and other uncharismatic animals* have to be killed to protect native ecosystems, we ought to find ways to do that that both have the intended effect and don’t cause unnecessary harm.

also, please no “humans are the invasive species” thing. I will hit you with my ecologist stick

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

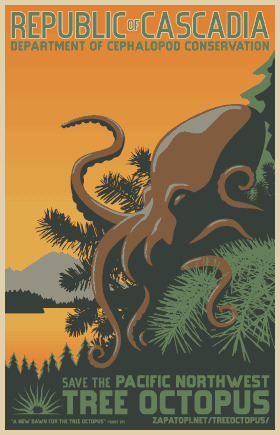

Today I want to talk about the Pacific Northwest Tree Octopus (Octopus paxarbolis).

OK, so for those who don't know, the PNW Tree Octopus was an internet hoax created in 1998 consisting of a website detailing the animal's life history and conservation efforts. It's completely fake - saying that up front. This animal never existed.

But if you look at this from a speculative biology standpoint? It's genius.

There is one, and only one, thing preventing Octopus from colonizing and being hugely successful in terrestrial environments in the PNW, and that's the fact that no cephalopod has ever been able to overcome the osmotic stress of inhabiting freshwater. We don't know why this is; other mollusks evolved freshwater forms just fine. But if you hand-wave away that one, single limiting factor, the PNW is just primed for a terrestrial octopus invasion.

The Pacific coast of North America is an active tectonic boundary, meaning the coast transitions pretty much immediately into the Cascade and Coastal mountain ranges (contrast with the east coast and its broad Atlantic plain). It's also a lush temperate rainforest, with very high precipitation. This means lots and lots of high-gradient mountain streams with lots of waterfalls and rapids and cold, highly oxygenated water, and not as many large, meandering rivers.

This has important consequences on the freshwater fauna. For one, there are not many freshwater fish in the Pacific Northwest - the rapids and waterfalls are extremely hard to traverse, so many mountain streams are fish-free. There also just isn't much fish diversity in the first place - there's sturgeon in the big rivers, salmonids, a few sculpin and cyprinids and... that's pretty much it. These cold northern rivers are positively impoverished compared to the thriving fish communities of the Mississippi or Rio Grande.

Few fish means few predators, and depending on the size of the first freshwater octopus, salmon and trout just wouldn't be much of a threat. And while these rivers don't have much in the way of fish diversity, there's lots of prey available - crayfish, leeches, mosquito larvae, frogs and tadpoles, water striders, and other aquatic insects, just to name a few. So the first Octopus pioneers to invade the rivers would be entering what essentially amounts to a predator-free environment with lots and lots of food and no competition. Great for colonization.

These ideal conditions get even better once you get up past the rapids and waterfalls, since there's no fish whatsoever in those streams. Octopus, with their sucker-lined arms, are perfectly equipped to navigate fast-moving, rocky-bedded streams and climb up cliffs. They'd also be well able to traverse short stretches of dry ground to access even more isolated pools and ponds. In fact, once Octopus overcome the osmoregulation problem there's nothing at all preventing them from colonizing land in earnest, since the PNW rainforests are so wet; there's no danger of drying out.

Finally there's the question of reproduction. Octopus are famously attentive mothers, because they need to keep the water around their eggs moving and well-oxygenated. In a mountain stream, this wouldn't be an issue, because the cold, turbulent water holds lots and lots of oxygen. Breeding in high mountain streams would be ideal, and the mothers might not even need to attend to their eggs, freeing them up to evolve away from semelparity and allowing them to reproduce more than once in their lives; their populations would thus increase rapidly and dramatically.

I think, if octopus managed to invade freshwater ecosystems in the PNW, it would dramatically change the ecology much like an invasive species. They'd be unstoppable predators of frogs, bugs, slugs, maybe even larger animals like snakes, birds, and small mammals. Nothing would eat them except maybe herons, and things like bears and raccoons would give them a wide berth due to their venom. They would rule that landscape.

The tl;dr is that the PNW is primed for invasion by cephalopods, if only they could manage to overcome the osmoregulation problem and live in freshwater. If the Pacific Northwest Tree Octopus really did exist, it wouldn't be a shy and reclusive species on the brink of extinction; it would be a pest, an invasive, overpopulated menace you couldn't get rid of if you wanted to. I can just imagine them crawling up onto people's bird feeders and either stealing the nuts or luring in unsuspecting sparrows and starlings. They would sit in the trees and throw pinecones at hikers for fun. They would be some unholy mixture of snake and slug with the personality of a magpie and I am incensed that they only exist in fiction.

#long post#octopus#speculative biology#speculative evolution#spec bio#spec evo#pacific northwest#pacific northwest tree octopus#truly a shame that there are no freshwater or terrestrial cephalopods

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

“These Were Salt Marshes Before” (2024)

11in x 14in acrylic on recycled canvas

“These Were Salt Marshes Before” was submitted and accepted by the SAA for the 18th Inspired by the PEM show! The reception went really well. I gained a lot of insight speaking with various artists about their pieces and how 'Our Time on Earth' inspired them.

In the case of this piece, it is inspired by the instant sense of calm 'Our Time on Earth' presents as one enters the exhibit. It’s The first instruction for the exhbit is to stop and breath. As I did so, I imagined a time when the place I stood was a coastal wetland. An type of ecosystem which once thrived along the East Coast of North America, rich in biodiversity and crucial for the region's ecological balance. However, centuries of urbanization and industrialization have devastated these wetlands, with many drained, filled, or paved over for development. Pollution from urban runoff and industry has further harmed remaining habitats. Only fragments of wetlands remain, threatened by sea-level rise, erosion, and ongoing development. Despite these challenges, recognizing the importance of wetlands as barriers against extreme weather and climate change, as well as their role in carbon storage, offers hope for their preservation. Protecting and restoring coastal wetlands not only safeguards biodiversity but also aids in mitigating climate change by sequestering carbon dioxide, contributing to global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Despite this train of thought I was not plunged into the usual dread over the future of our planet. It speaks to to power of these exhibits (and to media as well) that can address the biggest issue on the planet but still have radical, thoughtful, careful hope.

#acrylic painting#peabody essex museum#our time on earth#wetlands#climate change#climate justice#salt marshes#art of mine#artists on tumblr#contemporary art#fine art

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juniper | Juniperus Communis

A summary of the magical, medicinal, ecological properties.

Other names: Common Juniper

Distribution: The common Juniper has the largest geographical range of any woody plant, with a complete circumpolar distribution across the temperate Northern Hemisphere. It can be found from the mountains in the arctic, all the way south to thirty degrees latitude in North America, Europe and Asia. Small populations can be found in the Atlas mountains of North Africa. In North America it can be found in all of Canada and Alaska, and much of the Northern US, as well as in smaller populations throughout the US West.

Description: Common Juniper can look an array of different ways depending on where it's found, as the location determines the subspecies. It can range from a creeping shrub to a tall conifer tree, so it's highly recommended to look up which subspecies is/are local to you. Almost all subspecies do have the following in common, though: the leaves are green, needlelike, usually in whorls of three, and feature a white stomatal band through the middle. Juniper is dioecious; male cones are yellow, about 3mm long, and fall in spring. The fruit are cones (often mistaken for and referred to as berries), they show green initially but ripen to a purple black or blue black. They usually consist of three or six fleshy scales, each with one seed.

Ecology: The plant propagates when birds eat the berries and pass the seeds through dropping. It prefers sandy, rocky, or otherwise well-draining soil. It's associated with a variety of conifers, especially pines and firs. It's an especially important food source for birds, but doesn't receive much use from larger wildlife.

Myth and Legend: Juniper doesn't have a particularly strong presence in ancient mythology, which is surprising, considering its widespread nature and uses in medicine. It was thought for a while that Junipers were mentioned on several occasions in the Old Testament, but they mostly proved to be different plants. The only exception is 1 Kings 19:5-18, where the prophet Elijah shelters under a juniper while in hiding. So what's left? There is a small amount of much more local folklore about Juniper. In Germanic and Celtic regions, Juniper had an ancient history as sacred tree, and therefore was though to be unlucky, a fate that many formerly holy trees experience. One was not to plant a Juniper next to another unlucky tree, nor bring Juniper inside, nor chop it down without permission, as it was sure to bring catastrophy to the family. In the Germanic regions Junipers were passively associated with dwarves, as they were sometimes thought to have much knowledge about them. The yellow spores of Juniper, which sometimes travel through the woods in big clouds, were seen as a blessing upon the woods. There's a lot of Christianized Juniper folklore as well. That Christ's cross was made of Juniper (which would have been impossible), that he rose to heaven from atop a Juniper, that the voice of God commanded Christians not to fell Junipers, that Judas hanged himself from one, etc. These are all indications of holy status in the pagan faiths, which translated into the Christian era. Juniper is also sometimes portrayed as a tree of death and resurrection in European fairytales.

Religion: The Juniper plays only a passive symbolic role in Christianity as a tree of protection from persecutors. We can deduce from how the Juniper has persisted throughout time that it was once a sacred tree to the Germanic peoples. We know it was also sacred to Mediterranean pagans, especially the Romans and Hellenics. They would often substitute burning rosemary for burning Juniper for all matters to do with the underworld, death, and cthonic deities, and carve idols out of Juniper wood. It was also used for communication or summoning of monsters. Medea, priestess of Hekate, is said to have used it.

Magical Application: Juniper is quite prickly to the touch, and enjoys a status as spirit/demon-repelling plant for that reason. It is also fairly aromatic, which was also associated with repelling spirits. It is among the most famous protective plants in Europe, because of its many traits that make it so suitable. Juniper hung from doorways and the like was said to repel witches, and enchanting oneself with it would help one recognize them. All in all, a very strong protective and repellant plant, suitable for everything concerning keeping spirits away, and curing curses. It was also used for fertility rituals, especially in the continental Germanic regions. The way in which it was done was not up to snuff in terms of modern ethics (it was used as switch to beat the subject of the spell with, primarily), but it could still lend itself exceptionally well to fertility magic of all kinds. Because the plant is so sacred, it can easily be used to bless things or devote them to your Gods. It was also used in divination at times. Gin and other drinks made with Juniper berries were believed to make one more capable of divination or give prophetic dreams.

Magical Healing and Medicine: Juniper berries are rich in terpenes, volatile oils, tannins, sap and bitter components. It works as a disinfectant and diuretic, the latter function of which is the most crucial in folk medicine. Juniper leaves also harbor fungi which are stronly anti-fungal, which are now FDA approved to treat fungal infections. Much less scientifically, both Native Americans and Europeans have long used Juniper berries as a contraceptive and abortaficent. Since antiquity it has been prescribed to tone the uterus, or, in larger doses, cause "births under the saving Juniper," a euphemism for an intentional miscarriage. As medicine, because it was so magically repellent, it was especially well used to treat illnesses of a magical sort, but it might also be used for your usual remedies against fevers, warts, etc. Transfer magic would likely work well on Juniper trees. Juniper has a long history as healing plant and medicinal herb, definitely worth exploring.

Practical Applications: Juniper wood lends itself very well to carving. The berries are used to make Gin and other Juniper-based drinks, and are used a lot in cuisine. They aren't very good to eat raw, as they are quite bitter, but dried and crushed they are frequently used to improve stews, gamey meat, etc. Do not consume more than the equivalent of about 15 Juniper berries a day, as it could have negative side effects and cause damage to internal organs.

**This is a shortened version of the pages I offer on my ko-fi. You can commission any custom research project, but this is an extremely simplified version of my herbarium page. Please consider commissioning me if you would like to receive a much longer portfolio like this, with a source list, many more images, and much more information! I do custom discounts for repeat customers.

#apothecaric allerlei#herbarium#folk magic#folk witchcraft#witchblr#folk medicine#animism#plants and herbs#green witch#herbalism

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dear Charlie,

How do you feel about rewilding regions with species of Pokémon that haven't been present for thousands of years?

For reference, I don't mean fossil 'mons, but rather something closer to how the feral Rapidash populations in western Unova and Orre, descended from Paldean stock, have helped restore the grassland ecosystems after they went locally extinct during the last Ice Age.

//OOC: Didn't know if this ask hewed too close to the "no fakemon/fake region" rule. I was inspired by the "origin of Alolan Pokémon" ask from a while ago, as well as the historical reintroduction of horses to North America.

i don't really see much of a point to it unless there's an ecological need. environments change over time, and localized extinction is a normal aspect of natural ecosystem shifts. the environment might no longer be suitable for a pokemon that once lived there.

there are no rapidash in western unova. they're only found in a small area in the northeast, just outside of lacunosa, where their ecological impact is fairly negligent.

the presence of rapidash in orre is too recent to say much about the impact they're having. the region had no wild pokemon about 20 years ago, and there is only a small number of feral kantonian ponyta/rapidash in the region right now. my friend who works in ecological restoration in orre actually owns one of these rapidash after capturing it from the wild.

however, rapidash were never native to orre. although it was initially believed that old fossils were rapidash fossils, the current understanding is that it was actually an ancestor of the much hardier mudbray that once populated the area. rapidash aren't actually beneficial to orre's environment for a variety of reasons. they overgraze the delicate grasslands, which makes it difficult for actual native species to thrive and causes damage to the recovering ecosystem. their flames are also a fire hazard, which can be devastating in orre's dry desert environment. i think the current plan is to manage the population to prevent population increase until these feral herds die out, allowing for the mudbray to once again fill in. the mudbray are being brought back because they fulfill an important environment need, as they will dig out water pools that other pokemon can then use, without overgrazing or burning down the grasslands. they were still present in orre up until the extinction event that drove out its entire wild pokemon population, so their place in the orrean ecosystem has always existed.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bison are often associated with North America, but the wisent (Bison bonasus) is native to Europe. It was driven to extinction in the wild in the early 20th century (it had been extirpated from western Europe for several centuries), but reintroduction efforts began a few decades later.

As with American bison (Bison bison), the wisent is an important keystone species, and its reintroduction stands to benefit the ecosystems it is returning to. As browsers, wisent help keep plant growth in check, and their manure is valuable both for the plant community as well as detritivores and decomposers like various insects, fungi, and microbes. Native large carnivores are generally as scarce as the bison, but in places where wolves and other predators still exist, the bison could be important sources of food.

The hard truth about restoration ecology is that we will never be able to get ecosystems back to how they were before humans so heavily altered them. We can't even necessarily return them to when our impact was much lighter, given all the changes we have made. But if we can at least create pockets of biodiversity with safe travel corridors between them, that will go a long way in at least keeping native wildlife from disappearing entirely. The reintroduction of the wisent in Europe, and the bison in North America, represent important steps in undoing at least a little of the damage done.

#wisent#bison#bovidae#European bison#endangered species#extinction#ecology#restoration ecology#habitat restoration#keystone species#mammals#nature#wildlife#animals#environment#conservation#science#scicomm#rewilding

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other day I was talking to a friend who's a Muslim activist, and I made the connection between Amitav Ghosh's analysis of the climate crisis and my feelings about the genocide in Gaza and, more broadly, to the enforcement and regulation of inequality in our current moment. Ghosh refers to the way that we are living in the climate crisis as "the great derangement." There is a kind of collective madness, he argues, in the fact that we all know that climate change is happening and why it is happening and that every day we contribute to it happening, and yet at the same time climate change appears almost nowhere in our culture. We don't talk about it. We don't engage with it. Engaging it with would mean acknowledging that the premises on which our society is built are false and unsustainable. And the genocide in Gaza functions in a similar way: we know that it is happening and yet we don't talk about it or engage with it because it exposes the falseness and unsustainability of the premises of our society (premises that in this case include human rights).

I think that a lot of the things that Ghosh says illuminate how these two derangements are actually the same derangement, the derangement of what people in the environmental humanities have started calling the plantationocene. This has to do with a world ecology that sustains a hegemonic elite (and Eurocentric) modernity through the breakdown and (re)circulation of everything that is deemed to belong to the non- or subhuman. The world of the plantationocene is one that has always been defined by the ability of hegemonic power to treat both ("sub")human and nonhuman populations as interchangeable resources that can be deployed whenever and wherever they are most profitable to hegemonic powers: vide the relocation of African slaves and South Asian laborers, the disastrous ecological reshapings of colonized territories to better produce an elite European modernity.

To challenge what is happening in Gaza requires a challenge to several key principles of this world: that hegemonic elite modernity (which Israel has always formed a part of, as one can easily see by glancing at attempts to define the "Global North") has the right to regulate populations as it sees fit; that this regulation of populations is right because the sub-/nonhuman does not possess an unquantifiable wholeness that can be damaged or destroyed through civil destruction and forced relocation (i.e. it makes no difference to resettle indigenous peoples of the Americas or to transport South Asian laborers to islands halfway around the world, because their interchangeability means that nothing important is lost in the process— no more than transporting a plant to a different continent entails a loss or damage to the plant or botanical world); that the sub-/nonhuman exists as a resource to fuel, produce, and sustain hegemonic elite modernity, and can be simply wiped out if it becomes inconvenient or counterproductive to that modernity.

If you start to pursue these ideas, you realize that the genocide in Gaza is enmeshed in the "border crisis" and "refugee crisis" in Europe and the U.S.; you realize that all of these are enmeshed in your ability to walk into a superstore and purchase cheap consumer goods produced and assembled under inhuman conditions; it is enmeshed in everything you touch. And it becomes so overwhelming that you simply do not know how to think about it, because the suffering and the culpability for the suffering become so vast.

But we cannot let ourselves perpetuate this derangement. We have to look straight at the fact that it is absolutely insane that Gaza is no longer even the top headline on news sites. It is absolutely insane that Americans and Europeans (and even some Israelis!) can walk around and go through their days and not think about it at all. It is absolutely insane that we know what is happening and don't act. And I think that a lot of what Ghosh writes in The Great Derangement about the nature of contemporary politics explains why we don't act— but we have to live in the dissonance and tension of how absolutely insane it is that we don't act. We can't let the derangement trap us inside of it.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a link you can hold onto in case you ever need to tell somebody why reintroducing predators into North American ecosystems is important

After decades of high deer populations, North American forests have lost much of their previous biodiversity. Any landscape-level recovery requires substantial reductions in deer herds, but modern societies and wildlife management agencies appear unable to devise appropriate solutions to this chronic ecological and human health crisis. We evaluated the effectiveness of fertility control and hunting in reducing deer impacts at Cornell University. We estimated spring deer populations and planted Quercus rubraseedlings to assess deer browse pressure, rodent attack, and other factors compromising seedling performance. Oak seedlings protected in cages grew well, but deer annually browsed ≥60% of unprotected seedlings. Despite female sterilization rates of >90%, the deer population remained stable. Neither sterilization nor recreational hunting reduced deer browse rates and neither appears able to achieve reductions in deer populations or their impacts. We eliminated deer sterilization and recreational hunting in a core management area in favor of allowing volunteer archers to shoot deer over bait, including at night. This resulted in a substantial reduction in the deer population and a linear decline in browse rates as a function of spring deer abundance. Public trust stewardship of North American landscapes will require a fundamental overhaul in deer management to provide for a brighter future, and oak seedlings may be a promising metric to assess success. These changes will require intense public debate and may require new approaches such as regulated commercial hunting, natural dispersal, or intentional release of important deer predators (e.g., wolves and mountain lions). Such drastic changes in deer management will be highly controversial, and at present, likely difficult to implement in North America. However, the future of our forest ecosystems and their associated biodiversity will depend on evidence to guide change in landscape management and stewardship.

The deer are literally eating all the tree saplings in a lot of areas so the forest is having the old trees die and no new trees grow, and they're eating all the rare wildflowers like orchids and trilliums.

Human hunting doesn't work, and sterilizing more than 90% of female deer doesn't work. The answers the researchers propose are regulated commercial hunting (basically, hunting deer in limited amounts so the meat can be sold just like farmed beef or pork) and reintroducing wolves and mountain lions.

"Wolves and mountain lions are dangerous!" Out of an estimated 458 deadly encounters with animals that occur in the U.S.A. yearly, an estimated 440 of them are fatal collisions with deer.

Next time there is some dumbass Republican trying to claim wolves don't need to be protected by the Endangered Species Act (yes, they're literally claiming that wolves are fully recovered when they don't even exist in the vast majority of their former range) have these links close at hand

870 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's learn more about the impressive but potentially invasive ornamental plant introduced from North America, the Canadian Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis).

Despite its invasive nature, Canadian Goldenrod is an important food source for a wide range of insects including the Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus). Cattle and horses as well as deer can safely eat Canadian Goldenrod, and the flowers are not associated with allergies in humans since they do not produce airborne pollen. The plant is used in traditional herbal medicine by indigenous Americans for fevers and respiratory illnesses.

This gold-medallist invasive species has become an ecological menace in Europe and East Asia, where Chinese experts blame it for the extinction of over 30 species of native Chinese plants. In the UK, this admittedly attractive plant was introduced as an ornamental in the 19th century but it soon fell out of favour with gardeners because it was too aggressive.

I am unsure whether the Canadian Goldenrod in my garden is a survivor of a old garden design or if my late Dad added it to the garden, but it is confined as a specimen to a small patch in my garden. New plants are removed if found elsewhere on my property, so it won’t win any gold medals for invasiveness here.

#katia plant scientist#botany#plant biology#plants#plant science#yellow flowers#flowers#wildflowers#goldenrod#canadian goldenrod#plant identification#cottage garden#plant facts#north american plants#solidago#plant scientist#plantblr#gardening

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Political insiders like U.S. Rep. Dean Phillips have been expressing doubts about Joe Biden for years. Yet Biden just keeps winning. Voters have elected him to national office three times in four elections. Those voters also gave him the biggest midterm win for a Democratic president in 60 years. Biden has earned those votes by delivering the strongest domestic leadership since LBJ, and the strongest international leadership since JFK. He is the best candidate we have in 2024, and the only thing holding him back is the doubters in his own party.

The very fact that Biden was able to beat Donald Trump and be sworn into office in a peaceful transfer of power met an important test. Peaceful, you ask? Certainly former President Trump's actions, and those of his mob, were not peaceful. But Biden sailed through all of the calamity with apparent calm, acting as though there was never any question that the Constitution and the rule of law would prevail. He was always confident in us.

The immediate task of the new president was grappling with a nation divided over COVID and the need to provide economic support to families struggling through the pandemic. The American Rescue Plan put billions of dollars into the hands of working-class Americans. The economy boomed, driven by demand from workers and families spending money on necessities. Child poverty dropped by 40%, and American families have seen wages rise at levels not seen since the 1960s. Today, the strength of the American economy is pulling the rest of the world forward, despite the global struggle with inflation.

It is easy already to forget the size and scope of the Biden infrastructure bill, which will modernize American communities and our economy for a generation and more. Roads, bridges, transit, the electrical grid, water infrastructure, broadband — the whole platform for growth in the nation will be built out and create millions of American jobs.

Perhaps most significantly, Biden's so-called Inflation Reduction Act will transform our energy economy and enable America to meet its greenhouse gas reduction goals. This will put us in the driver's seat for pushing other nations to meet their goals. There is no larger threat to our nation and the global economy than rising global temperatures, increased severe weather and the loss of a precious ecological and cultural heritage. The pandemic was a light breeze compared to the impending storm of global climate destruction, and the Inflation Reduction Act was a strategic move to allow us to lead in stopping it.

The Inflation Reduction Act could also be called the Chinese Divestment Act. Not only does the energy policy address our need to transition to renewable energy, but it creates enormous incentives for companies to invest in technology and manufacturing in North America. No other president in our lifetime would offer an American working family $7,000 to buy an electric car made in America. The Inflation Reduction Act is exactly the industrial policy this country has needed for so long.

Just a few years ago, Chinese economic power coupled with Russian weapons of war appeared to be a genuine threat to the American-led international order. Autocrats were rising while traditional Western democratic institutions were in disarray. Some people were comparing America to Weimar Germany and seeing similarities to the weakness of democratic nations in the face of fascism.

Russia's illegal and inhumane invasion of Ukraine came at exactly the wrong time — for Russia and China. Putin threw down an enormous challenge in front of the American-led alliance. We advanced as one against him. Biden worked with Europe to accept major economic pain as a price of confronting Russian aggression. The Biden response to Russian aggression simultaneously revived the democracies' power in the world and reminded us that autocracies are always fundamentally weak.

In just three years, Joe Biden's leadership has revived democracy, defeated a pandemic, raised millions of Americans out of poverty, revitalized American infrastructure, addressed global warming and weakened authoritarian nations. He also keeps winning elections and confounding all his critics. Congressman Phillips: What more do you want?

Ryan Winkler, of Golden Valley, is the former DFL majority leader of the Minnesota House.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scolia bicincta!!!! gardener getting excited!!!!!!

if youve ever tried to grow anything in most of north america then you probably know about my worst nightmare and mortal enemy the japanese beetle. basically theyre shiny little fuckers who eat EVERYTHING and come in swarms. and there are very few ways to manage them that dont involve ecological devastation over a single critter. EXCEPT MY BEST FRIEND SCOLIA BICINCTA (AND OTHER SCOLIIDS) THEY EAT THEM!!!! AND THEYRE GOOD AT IT TOO. FUCK YEAH

not as adults tho- the adults are pollinators that spend their time searching for flowers and mates and somehow (???) sensing the presence of japanese beetle grubs and other scarab larvae. then they dig down into the grubs chamber and lay eggs on them that hatch into little baby wasps that burrow into the grub and eat it alive- they eat the least essential organs first to keep the rest of it fresh for longer- and then once theyve stored enough food, like a caterpillar, they transform into adult wasps, emerge from the dead grub, and dig up to the surface to fly away and mate and live their lives pollinating flowers and saving trees and gardens. also theyre so pretty their wings are like purpley and iridescent and its hard to get a picture of so just go look at them irl-

a few years ago, when i started my garden, japanese beetles would appear in massive numbers every summer and undo all the progress i had worked so hard on. but then i learned about native plants and wasps and i planted a patch of mountain mint (SCOLIIDS FAV❗❗❗) and let the lawn grow tall to create habitat. and this year is the first time the beetles were literally negligible. ive seen like two or three all summer. mountain mint alone can do so so so much for the ecosystem i dont even have a lot and if youre in its native range i truly cannot recommend highly enough that you plant it. theres a few different species so you can probably find one adapted to your garden. its so good and so important seriously

ALSO ANOTHER TIP IS JAPANESE BEETLE GRUBS FAV FOOD IS THE ROOTS OF LAWN GRASS WERE LITERALLY FARMING THEM AND THEN GETTING MAD THAT THEY EAT OUR VEGGIES. PLANT NATIVE PLANTS FUCK LAWNS

#plants#gardening#native plants#flowers#ecosystems#bugs#wasps#japanese beetle#scoliidae#mountain mint#pycnanthemum#ecology#organic#tw bugs#lawns#fuck lawns

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Heyyy from one very tired jew to another

.. I wanna learn more about ecology! I wish we were using all our collective energy into saving planet instead *everything else*.

Do you work in that space? How would you recommend getting more involved? Or just wanting to learn more/nerd out about it?

So the thing is, there's a whole swath of people working on this.

There's so much research and application going on that does not get talked about because it's not "sexy" science. It doesn't make the news because it's not big world changing once in a lifetime advancements, it's little things that address a problem here or there that collectively make an impact. E.g. there is now research going into various blow flies (Calliphoridae) as pollinators. I know of 5 different entomologists in the world doing this. It's not making the news because flies are not "sexy" and don't need to be "saved". Flies are also considered gross, but according to one of my colleagues who is working on this they're major pollinators of things like onions, mangos, garlic, other crops, and non-crop plants that are important. Understanding their pollinator ecology let's us better understand how they interact with their environment, how they benefit it, and what we can do to better improve those benefits and thus address some of the negative impacts we have.

In regards to actually getting involved, that depends on what level of involvement you want. There are citizen science projects out there that necessitate non-scientists to collect data locally and send it back to the primary researcher for analysis.

There are extension offices that have educational materials and extension officers who give talks.

There are usually outreach events by ecology or entomology departments from big name colleges that can be attended.

There are, obviously, books on the topic. But I personally don't like them to become educated on things outside of textbooks as the nonfiction non-textbooks that we consider "pop science" usually have a singular author's bias or agenda in the text and are overly simplified. Honestly, if anyone suggests a pop science book to you just walk away. They're rarely good from a professional perspective.

Then you have to also think about what you're interested in as well.

Insect ecology? Reptiles? Freshwater? Marine? Physiological? Agricultural? and many more.

There's a lot of subfields to ecology and each of them have their own particular interests, projects, personnel, and so on.

Some universities might have the ability to audit or take a course for free if you're simply curious.

Also consider that local ecology is going to be different, so you might find online resources or information for ecology relating to the North East USA, but you live in the Midwest. Well things like the River Continuum Concept aren't really applicable to the Midwest as the theory was designed for rocky bottom water systems, not the sandy/soil based ones in America's FarmlandTM.

7 notes

·

View notes